To anyone that says, "A randomized controlled trial in nutrition is impossible!" I can now say, "You just don’t want it badly enough."

Should you go on the Mediterranean diet?

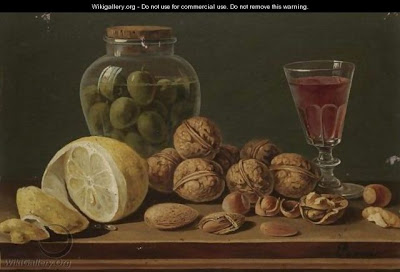

Should you go on the Mediterranean diet?As you are already probably aware, the Mediterranean diet is one of the diets that started it all. Its rules are relatively simple: lots of olive oil, lots of fruits and nuts, lots of vegetables and cereals, and some fish and chicken, and not a lot of dairy, red meat, processed meats, and sweets and some wine (And while Greece is part of Mediterranean, Greek yoghurt does not seem to feature prominently in this diet–so think on that a bit…)

The Mediterranean diet has been studied a lot. One could argue that of all the diets that have gone though fad phases, including the Atkin’s diet, the Mediterranean diet has been studied the most. In particular, its effects on preventing cardiovascular events (stroke, heart attacks and death from either) has been of particular interest. There have been major cohort studies, but never a randomized controlled trial.

Today, the PREDIMED trial was published in the New England Journal of Medicine. And yes, I’m all drooly over it. I’m totally gaga over the fact that the full study protocol was published in an appendix. It’s awesome. So, let’s cut to the meat of the matter:

Estruch R et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. New England Journal of Medicine. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM200303, published February 25, 3013 at NEJM.org.

Methods:

To say that this is a complicated trial by design would be wrong. It’s not complicated, even though the statistics may appear that way. What IS complicated is the sheer logistics of doing a multi-centre trial on this scale; as well as the sheer amount of information published in this paper (they are going to be publishing follow-up studies on this trial for YEARS). I’m not even going to try to get through all of it; but I hope to share with you the important take-away points.

In some ways, this trial is not unlike the “Red Meat Will Kill You” cohort study. That is to say, the people that it is supposed to help is not as wide a population as one might think. And while the title of the paper would suggest that it could help everyone, it’s clear from the methods that it doesn’t; nor was it designed to do so. I’m going to break it down further than normal for this reason.

Target population:

To be eligible for this study, subjects had to be men between the ages of 55 and 80, or women between 60 and 80. They had to have no cardiovascular disease when they started in the study, but they did have to have type II diabetes OR at least three of the following conditions:

1) Smoking

2) Hypertension

3) Elevated LDL cholesterol levels (> 160mg/dl)

4) Low HDL cholesterol levels (<= 40mg/dl)

5) BMI >= 25

6) Family history of coronary heart disease

Potential subjects were excluded for a wide variety of reasons, some of which included:

1) Any medical condition with a survival expectancy of less than 1 year

2) BMI > 40

3) Difficulties or major inconvenience to change dietary habits, or a low predicted likelihood to change dietary habits

4) Allergy to nuts, or olive oil, or inability to eat (e.g. swallowing disorder) or dietary restriction against adopting a Mediterranean diet (for obvious reasons)

5) HIV or immunodeficiency

I started this section with a description of the target population because I think this is the biggest “limitation” (which isn’t really a limitation) of the study. If you don’t fit in this eligibility category, then this study doesn’t apply to you. No matter how great or horrible it is (and trust me, it’s not horrible) I think it’s very important to understand the limits of generalizability on this study. So if you wouldn’t otherwise have been eligible for this study, and you came here wanting to know if you should be buying more olive oil and nuts, you can pretty much stop reading here–unless you’re SUPER nerdy and want to keep going for fun.

Interventions

No matter which group subjects were assigned to, there were no explicit caloric restrictions on any of the diets. That is, subjects were not instructed to reduce calories or to attempt to meet any kind of caloric deficit. If they did, it was just a result of the diet they were on. Subjects that met the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to one of three groups:

1) Control group

This group received a leaflet on guidelines for a low-fat diet. Three years into the study, they also received personalized advice and group sessions that were provided to the other two groups, but focussed on the low-fat diet. They were also given a dietary screener to see how well they were sticking to the low-fat diet at these sessions. Since the other two groups were getting food gifts as part of their intervention, the control groups received, “nonfood gifts” instead.

2) Olive oil group

This group received personalized and group sessions on the Mediterranean diet. They were also given a dietary screener to see who well they were sticking to their diet. In addition, they also received about 1 litre of extra-virgin olive oil every week, which was donated by two olive oil producers in Spain. A random sample of people in this group had urine testing at 1, 3 and 5 years for hydroxytyrosol, which is a marker for olive oil consumption.

3) Nut group

This group also received the personalized and group sessions on the Mediterranean diet with the screeners. Instead of olive oil, they were given 30g of mixed nuts (15g of walnuts, 7.5g of hazelnuts and 7.5g of almonds) per day. The walnuts were donated by the California Walnut Commission, and the hazelnuts by a Spanish nut company. A random sample of people in this group had blood tests for alpha-linolenic acid at 1, 3 and 5 years, which is a marker for nut consumption.

So, back to generalizability and the research question. I think it’s important to note that this is NOT a trial of the Mediterranean diet against “regular” diets. The control group still received an intervention. They modified their diet from whatever it was to a low-fat diet.

First point: This is a comparison of two variants of the Mediterranean diet with a LOW-FAT diet. If you’re trying to decide whether to go on the Mediterranean diet vs sticking with your current, not-low-fat diet, this trial does not apply directly to you. I’m not going to get into the nitty gritty details of what makes a diet low-fat, or what the low-fat diet was in this study, because this blog post is going to be long enough without it.

Second point: This is also not a “let them go free” trial. Even though they were three years late in the control group, all subjects were offered regular support and education every four months for the duration of the trial. This probably has an effect on diet adherence, which may or may not be an issue, since, if you’re able to stick to a diet on your own and periodically review your own diet in a relatively non-biased manner, it probably doesn’t matter if you’re in a support group or not.

Third point: I love the fact that the suppliers of the food gifts are named in this study. I also appreciated the statement that none of the sponsors of the trial had any role in the trial design, data analysis or reporting. I don’t think that industry involvement automatically taints a study. I just think that their involvement should be fully transparent and reported so that readers can make up their own minds.

Outcomes

The primary variable of interest was whether subjects had any of: a) a heart attack that didn’t kill them, b) a stroke that didn’t kill them, or c) a heart attack or a stroke that DID kill them. They also collected data on death rates in general from any cause in all of the groups.

Again, it’s important to note that “benefit” in this trial is being defined as a reduction in heart attacks and strokes. This trial doesn’t measure whether diabetes got better, whether high blood pressure got better, or whether there was a reduction in cancer rates, or being struck by lightning. In being able to answer the question, “Is the Mediterranean diet healthier?” it does a great job, provided you restrict “health” to heart attacks and strokes.

Statistics

This gets a little complicated because the designers of this study were really smart. They pre-planned interim analyses to figure out if they could stop the trial early. The total duration of this trial would have been 4 years if every subject could have been enrolled at exactly the same time. However, that’s not how real life works; particularly when you estimate needing 9000 patients. I’m not going to get into the specifics of how you plan interim analyses, but it shows great foresight and planning when you’re designing a large-scale randomized trial. Suffice it to say that they met the stopping criteria after 7 years (and I’m pretty sure July 22, 2011 was a day of much drinking)

The trial data was analyzed using survival analysis with Cox regression models. That’s all I’m going to say on that because it probably doesn’t mean a lot to most of you. To me, it’s just sexy.

Results

Still with me?

A total of 8713 subjects were screened for the study. Of those, 7447 were randomly allocated to one of the three groups. Of THOSE, 209 subjects didn’t show up ever again after their first visit. The total drop-out rate in the control group was 11.3%, and 4.9% in the Mediterranean groups combined. People who dropped out tended to be younger (by about 1.4 years), heavier (by about 0.4 BMI’s), and lower diet adherence.

The median follow-up time was 4.8 years. So, 50% of subjects had follow-up times more than 4.8 years, and 50%, less than 4.8 years. The upper limit of follow-up time would have been 7 years.

A total of 288 events occurred across the three groups (heart attack or stroke, or death from heart attack or stroke). In the control group, 109 events (4.4%). In the oil group, 96 events (3.8%) and in the nut group, 83 events (3.4%). These are obviously prone to lag-time bias, so the survival analysis does help things out a little bit here.

And just because I know it’s going to come up, I dug into the appendices of this paper:

“Macros”

1) Total energy was lower in the low-fat group than the other two groups (by about 200-260 calories.) All the diets were pretty close to 2100 calories per day roughly (they did not provide calories per body mass.)

2) The low-fat group had the largest mean reduction in calories (227 calories vs 47 in the nut group and 85 in the oil group.)

3) Total protein (as calculated by % calories) was higher in the low-fat group than the other two groups (by 0.7-0.9%). Protein comprised 16-17% of total calories for all three groups.

4) Total carbs (as calculated by % calories) were higher in the low-fat group than the other two groups (by 3-4%). Carbs comprised 40-44% of total calories across all three groups.

5) Total fat (as calculated by % calories) was lower in the low-fat group than the other two groups (by 4.2-4.5%). Fat comprised 37-42% of total calories across all three groups.

All of these differences would be statistically significant by virtue of the massive sample size. I’m not sure I would consider the differences that meaningful though.

In terms of a reduction of risk, the unadjusted hazard ratios (which is a relative comparison with the low-fat diet being the reference point), were 0.70 in the oil group (95%CI 0.53 to 0.91) and 0.70 in the nut group (95%CI 0.53 to 0.94), both of which were statistically significant using a likelihood ratio test.

After making adjustments for things like gender, smoking status, and age (and other stuff), it appears that the major risk reduction in adopting the Mediterranean diet compared to a low-fat diet is in the reduction of stroke. In terms of heart attacks, and death from stroke or heart attack, or death from any cause, the researchers failed to detect a statistically significant difference in those rates (adjusted both for person-years and for covariates.)

What’s really interesting is the subgroup analysis looking at the effect of baseline BMI on the hazard ratio, which shows a clear risk reduction for subjects with BMI>30, but no statistically significant effect for people with less than a BMI of 25. The test for interaction in this sub-analysis had a p-value of 0.05, which suggests a substantial difference in effect that is dependent on starting BMI (i.e. the risk reduction may only be present if you start at a BMI of 30–possibly because the control rate might be higher because those people tend to be sicker.) Interpreting a subgroup analysis, however, should always be done with caution because it may not be powered to answer that question definitively.

Interpretation:

First off, I think the investigators deserve a HUGE pat on the back for accomplishing an incredible feat. The things that made this study design possible was the fact that they had a very defined research question and (by trial literature standards) a simple analysis plan. This trial does have limitations, but I don’t think they crush any of the conclusions in any substantive way. Most important, it does successfully answer the research question it set out to answer (which is not something all trials manage to do.)

I think if you’re male, over 70 years old, with diabetes, high cholesterol and high blood pressure, this study shows that going on a Mediterranean diet very likely has benefit for you over a low-fat diet. That being said, if you’re male, over 70 years old with diabetes, high cholesterol and high blood pressure, you’re a pretty sick puppy to begin with, and even though a Mediterranean diet would be _better_ than a low-fat one, changing your diet to just about anything other than the one you were on to get to where you are now is probably beneficial (as long as you’re not changing it to cigarettes and donuts.)

I think that even if you’re just within the target population of this study (as opposed to being at highest risk within the target population), it’s important to note that going on a low-fat diet doesn’t give you the best risk reduction when it comes to heart attacks and stroke.

And again, if you’re NOT within the target population, this study doesn’t really apply to you until such a time that you are (which is hopefully never).