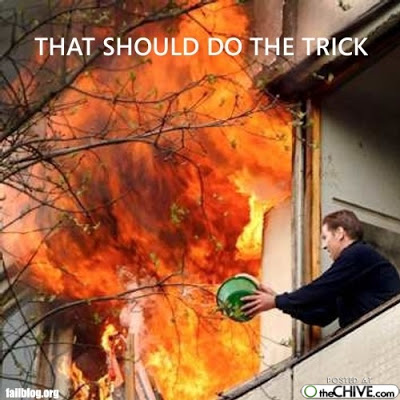

You don’t add higher octane gas to the house that’s on fire to put it out.

The World Health Organization’s definition of health, which I had to memorize in the first month of medical school, is, “The state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”

Personally, I think this is ridiculous because it’s basically tautological. The term “well-being” is essentially synonymous with “health”. In fact, the Merriam-Webster dictionary defines “well-being” as, “The state of being happy, healthy or prosperous.” Way to go, 1948 WHO’er’s. It’s like looking in the dictionary for the definition of “happy” and seeing “not sad” and then looking up “sad” and seeing its definition as “not happy.” (Flashbacks to being the child of immigrant parents inserted here. And yes, I was a weird kid and yes, my parents will tell you that.)

(Incidentally, the WHO definition of health hasn’t been modified since 1948.)

So, since the World HEALTH Organization has no satisfactory definition of health, it’s basically a free-for-all. Which means…ANYTHING can be sold to be healthy for you, up to, and including chocolate.

As a physician, I’m already terribly uncomfortable when people start talking about being “healthier”. As a scientist, I’m downright squirmy when it comes to trying to measure “healthier”. Put the two together and I may as well be wearing pants made of a cotton/fire-ant blend (thank you, Big Bang Theory.) In the scientific literature, health is basically measured in one of two major ways: Mortality (if you live longer, you must be healthier), and quality of life (if you live…ugh, “happier”, your longevity might not mean as much.) There’s a whole field of study that looks at how people would consider trading off years of their life for higher “quality” of life.

For most people that I interact/socialize with, it seems that “health” and “health-related-happy” comes down to function, “I want to be able to do the things I want to do without my body failing me.” These things generally entail: playing with my kids, lifting my (young) kids during play, going for a run, going to the gym, doing my job, handicrafts, and golfing (which comes up a lot, oddly for an activity that seems to be rife with frustration). “Playing with my kids,” is a really common one. “Bench pressing two times my body weight” not so much. “Training so that I can compete in the next Olympics,” oddly, has come up more often than “Bench pressing two times my body weight,” but that’s probably just my experience.

For a minority of patients, the definition is slightly different: “I just don’t want to get any worse,” and sometimes (sadly, yet usually and unexpectedly not), “I’ve had a good life, and I’m ready to go now.” “Health” is generally _not_ measured in years of life. Studies that earnestly use mortality as a primary outcome use it as a proxy for quality (e.g. if you had a heart attack that would have otherwise KILLED you, any additional time that can be achieved is better quality than dead-years, as contrasted from life-years. Or so we assume.)

I started this blog 5-ish years ago (long–year-long gaps notwithstanding.) Before I started this blog, I was a regular poster on JPFitness.com, before that, on Men’s Health, and before THAT I made regular contributions to ancient Internet tools like listserv’s and mailing lists (I think I just totally dated myself there.) What I would post now, is obviously a lot different than I what I posted back then (probably). I’ve also noticed a lot of trends come and go. Contrarian posting (e.g. Why you should never do that thing everyone’s been doing, like a bench press) has never gone out of style. Stability ball training has definitely had its hey-day.

However, one thing that hasn’t changed, even a little bit, is the idea that consuming different foods has inherent “health benefits”. Margarine good, butter bad. Fat bad, protein good. Ginger good. Tumeric good. Blueberries good. Cheese bad. Coffee bad but sometimes good. Chocolate milk good. Red wine good, but we lied about it. Spinach still good. Food as “medicine” isn’t new. Herbalism isn’t new. It’s practically household in most Chinese families, dating back a bajillion years (my mommy told me so).

If I look back at fitness magazines from when I was 16 compared to the fitness magazines now, the ubiquitous list of power/health/revitalizaing/fat-burning/muscle-building/anti-inflammatory/disease-preventing/AWESOME foods has never gone away. The foods have changed a little, but not a lot. (Hmm, there’s a study in that somewhere…) And while sometimes, they’re targeted at alleviating some sort of symptom, almost always they’re targeted at increasing years of life (Which we already know, is probably the _least_ helpful indicator of “health”, if we had to try to define it from what it isn’t.)

If a client comes to a trainer and says, “I want to be able to clean and press 100 pounds,” but is unable to bend down (in any fashion) to pick the bar up off the ground without pain, the solution is not to critique their clean-and-press form (“You know, you could clean-and-press way better if you weren’t whimpering in pain when you bend down…”). But the solution to too much food, is more food, just different food?

The idea that you solve a problem with more of the problem (just slightly different) strikes me as taking a backassward approach to the problem. If your problem is fat, and therefore eating, then changing what you eat isn’t really the optimal answer. You don’t pour a higher quality oil on a fire to put it out. Nor do you use distilled water if regular hydrant water isn’t working. If your problem is eating, then getting at why you eat is probably more productive; which is still probably less important than learning how to NOT eat (which is different, but not distinct from fasting–before someone jumps all over that.)

If your “health” is already pretty optimal, then it begs the question of whether you can be “supra-optimally healthy” (oh, there’s another blog post in the tube–the whole topic of “prevention”.) Will adding ginger to your diet make you _more optimal_? Will _going out of your way_ to add ginger to your diet make you _more optimal_? What if you don’t even like ginger, unless it’s in a cookie or an ale? And the kicker question, “If you DON’T eat ginger, are you LESS healthy?”

“Health” is a subjective state and fluid through one’s life. For some, it’s about living another year to see a child graduate from high school, or losing 50 pounds so they can qualify for a knee replacement. For others, it’s about finishing an Ironman. For some, those are applicable to the SAME individual at different stages of life. For every decision you make to pursue one thing, you inevitably trade off something else–just maybe not now. Sometimes, it’s a willing sacrifice, and other times, it’s unforeseen. I, personally, HURT people in my profession with the understanding that it’s a price that is worth paying for a larger payoff. And I don’t mean yelling at them to do another burpee, or pushing on a trigger point.

The problem with the list of superfoods, from my perspective, is three-fold:

1) It conditions us to believe that the problem lies not in the act/culture of eating but in the substance of the eating, (You are what you eat, and if you eat nothing, you are nothing?)

2) It introduces a false belief that all disease is modifiable (i.e. the supreme state of “health” is achieveable) if you could only combat all those oxidants, and inflammations and just get ALL those ducks in a row (which if you really think about it, is such horsesh@t; I mean, what if you run out of oxidants? Again, thank you, Big Bang Theory). It also insinuates the idea that you are MORE likely to succumb to a disease state if you’re NOT actively trying to prevent it (Is it possible to be lycopene deficient?)

3) It re-enforces the belief that spending more (energy/money/time/consumption) is the key to fixing what ails us; that there is a missing thing–a 1 that will fix everything, when, in fact, you don’t need another 1; You need a 0.

We’re coming up on New Year’s, which means resolutions for change. So before you decide to ADD something to your lifestyle, think about what you can take away first. Added complexity is seldom the answer–which is one of the reasons why adherence to new prescription medications is often so poor. As in house-cleaning, getting rid of things generally costs either very little or nothing, and makes room for more later when you really need the space for what you really want.