The State of Evidence-Based Fitness

I wanted to start my new site with a new post, but as with everything on this site, I get most of my blogging ideas from other people. I got the idea to write this entry from The Oatmeal’s “State of the Web”. Unfortunately, I have the drawing ability of Matthew Inman’s dog (this is debateable as I’m just surmising that his dog can’t draw very well). So you just get text with no nifty comic. 🙁

When I started this blog in 2007, things were a lot different. My very first blog post [Archived here] was inspired by a friend who had made the decision to move his workouts to the morning (because he had heard that working out in the morning was better for fat burning), but had also decided to get up an hour early so that he could eat something before his workout (because a) didn’t like working out on an empty stomach and b) had also heard that you shouldn’t) thereby single-handedly undoing the “rationale” of working out first thing in the morning.

Fast forward to 2013, and nowadays, we’re talking about whether or not to train in a fasted state, and at what caloric limit one could still consider it still “fasting”.

Hmm, I guess things are not that different.

Back then, Facebook had just started. I’m pretty sure there was no Twitter. Idea exchanges happened mostly through internet forums, and I had never even heard of Reddit. More importantly, not many people were asking questions about where their information was coming from.

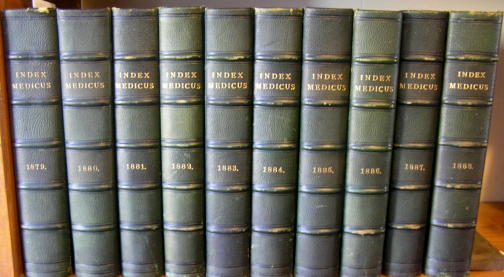

I remember when I was in my undergrad, having to trek to the library and HAND SEARCH the Index Medicus year by year. I remember when “Medline” became a CD-ROM that was delivered, like a magazine, to the library every month and having to wait for the ONE COMPUTER to be free to ELECTRONICALLY search it. And I remember how happy I was when Medline went online in the library, and then eventually from home through the password protected library website. I still remember going to the library, grabbing a trolley and pushing it from the A’s to the Z’s in the journal section and the into the photocopy room and copying articles so that two pages could fit on one page to save on photocopying costs. Back then, scientific knowledge wasn’t pubically inaccessible. It was the domain of scientists and downtrodden undergrads and grad students. Even in academia, it was basically an afternoon’s worth of work (because let’s face it, no self-respecting grad student gets up early enough to make it a morning if they don’t have to) to get journal articles.

I remember when I was in my undergrad, having to trek to the library and HAND SEARCH the Index Medicus year by year. I remember when “Medline” became a CD-ROM that was delivered, like a magazine, to the library every month and having to wait for the ONE COMPUTER to be free to ELECTRONICALLY search it. And I remember how happy I was when Medline went online in the library, and then eventually from home through the password protected library website. I still remember going to the library, grabbing a trolley and pushing it from the A’s to the Z’s in the journal section and the into the photocopy room and copying articles so that two pages could fit on one page to save on photocopying costs. Back then, scientific knowledge wasn’t pubically inaccessible. It was the domain of scientists and downtrodden undergrads and grad students. Even in academia, it was basically an afternoon’s worth of work (because let’s face it, no self-respecting grad student gets up early enough to make it a morning if they don’t have to) to get journal articles.

I remember the first time I downloaded a PDF journal article from home. It might have rivaled losing my virginity.

And then, PubMed happened, and the Index Medicus REALLY went public. A fully searchable, remotely accessible database of almost every medical journal article published since the invention of the medical journal became available to EVERYONE (with Internet access.)

I view this “informatic leap” with a slightly jaded eye. On the one hand, I think removing obstacles to knowledge is necessary and good. It has the potential to ignite innovation and discovery in people who might not otherwise have made contributions to the global body of knowledge that (I hope) moves us, as a species, forward. It is also important, from a funding point of view, that people are able to see (even if it’s not all at once) how their research dollars are being spent, since many of these studies are publically funded, or funded through charitable organziations.

The obstacle that remains, is, of course, full-paper access; which is slowly changing with open-access journals such as PLoS and collections like BioMed Central, but by and large, full access is still the province of those living in (or visiting) Academia-land. But even if we all had full-access to all papers ever published, I wonder if that would actually change much.

Barriers to access to full-text aside, however, the ease at which this information can be accessed has made it possible for the curious to really get their nerditude on. And more nerds can’t be a bad thing, especially now that they’re trendy (wait, does that make me an inadvertent hipster?)

My jaded eye is, by definition, more cynical. There’s some kernel of truth in every adage, and the saying, “A little bit of knowledge is a dangerous thing,” is one that I think we should heed. As evidenced by Romeo and Juliet, misunderstanding of a small detail (like knowing a death-like state from actual death) leads to tragedy for everyone. Scientists, by and large, view each others’ work with a critical eye, (hopefully) able to distinguish that which is useful and important from that which is not. We all live in the same “publish or perish” ecosystem and experience how the the nuances of that rule of the academic jungle colour the literature. But the casual safari tourist doesn’t have the same experience; and while the jungle is available for everyone to enjoy, it doesn’t mean that the brightly coloured berry picked for its beauty, sweetness, and near-identical appearance of a raspberry, doesn’t contain within it, a vomit-inducing toxin.

My jaded eye is, by definition, more cynical. There’s some kernel of truth in every adage, and the saying, “A little bit of knowledge is a dangerous thing,” is one that I think we should heed. As evidenced by Romeo and Juliet, misunderstanding of a small detail (like knowing a death-like state from actual death) leads to tragedy for everyone. Scientists, by and large, view each others’ work with a critical eye, (hopefully) able to distinguish that which is useful and important from that which is not. We all live in the same “publish or perish” ecosystem and experience how the the nuances of that rule of the academic jungle colour the literature. But the casual safari tourist doesn’t have the same experience; and while the jungle is available for everyone to enjoy, it doesn’t mean that the brightly coloured berry picked for its beauty, sweetness, and near-identical appearance of a raspberry, doesn’t contain within it, a vomit-inducing toxin.

A side-effect of PubMed has been the evolution of the ‘informed consumer’. To be honest, I’m not even sure if it’s a side-effect of PubMed, or a larger cultural, generational shift from the Baby Boomers (with one definiting feature of “Question authority”) to Gen X’er (who arguably might have taken it one step further to “Trust no one.”) It’s not good enough, for many, to simply “do as I did”, and this has created a market pressure to, “Prove it.” Enter, the use of “scientific study”, which is facilitated by the wide-spread access to PubMed and the conveniently short summary nature of the Abstract, which I’ve written about before. This has also spawned a new phenomenon of “science as entertainment”, which further confuses things because it’s difficult to tell, “Well, isn’t this just amusingly interesting, haha,” from “This is actually important,” because they look identical over social media sharing.

Information consumption today, is literally less than one click away. We’ve moved from a culture where knowledge was something you had to actively search and find to one where “knowledge bombs” are indiscriminately dropped in carpet fashion on unsuspecting consumers, creating problems where they might not even exist. After all, there’s no better market than the one you create.

So the state of evidence-based fitness today, from where I sit is a lot like a marketplace of juice vendors who basically all look the same on the outside. It’s virtually impossible to tell who’s selling juice squeezed from raspberries and who’s selling juice from vomit-berries; and most of the inhabitants of the jungle are too busy in the jungle to pay attention to the folks using their berries for profit. I would argue that it’s not so much the need for science-based justification for the behaviours we change and the things we eat, but that the ability to differentiate between appropriate and either unknowingly inappropriate, or worse yet, actively deceptive justification that is lacking today.

Now I’m going to go out on a limb and make myself unpopular with everyone who probably doesn’t need to read this: What’s lacking in evidence-based fitness has virtually nothing to do with evidence. There is, in fact, a glut of “evidence”. What is lacking in the fitness industry is professionalism.

I read a passing tweet last week, which ultimately is attributable to the American Board of Medical Specialties. They have a one-sentence definition of professionalism, which is, “Medical professionalism is the assertion that doctors are worthy of public and patient trust.” It’s actually a very succinct and apt defintion that encompasses a whole multiude of components. It implies not only an obligation to acquire knowledge, but to maintain a certain standard of it, and also to recognize ones limitations as experts on a body of knowledge that requires dedicated study as well as its appropriate application. It recognizes that patients often _don’t_ know as much and _do_ require help making sense of their condition(s) and that possessing this knowledge is a position of trust. Patients trust that doctors will help them make the decision that is right for them, because as smart and studious as some of them are, you just can’t replace 8-12 years of dedicated learning.

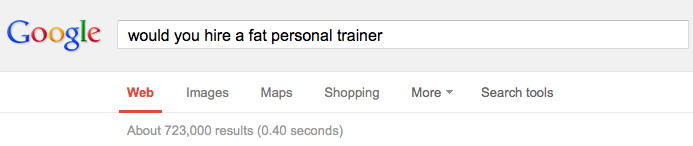

This isn’t to say that my profession has universally attained these lofty ideals (we’re all shooting for perfection here), but that if one were to re-state the phrase with “Fitness professionalism is the assertion that fitness professionals are worthy of public and client trust,” I’m not sure that I would give the fitness world a very high score, even with the given that most fitness professionals are well-intentioned. The barrier to enter and attain the title, “fitness professional” (in the coloquial sense) is very low. Distinction in the fitness industry can be attained not just through merit, but also through through viral messaging, sensationalism and appearance.  An industry where the question, “Would you hire a trainer that doesn’t look jacked/ripped/fit/toned?” can actually be considered a valid topic of debate only speaks to the lack of a bare-bones professional standard to which a person CAN actually trust a trainer. What to do about it? I can’t say that I know, which is by far, the most irritating position I can think of to take. So I apologize for being unproductive for whining about something I don’t know how to fix.

An industry where the question, “Would you hire a trainer that doesn’t look jacked/ripped/fit/toned?” can actually be considered a valid topic of debate only speaks to the lack of a bare-bones professional standard to which a person CAN actually trust a trainer. What to do about it? I can’t say that I know, which is by far, the most irritating position I can think of to take. So I apologize for being unproductive for whining about something I don’t know how to fix.

The foundation of my blog is about finding and revealing evidence (or its lack thereof) on topics that affect your fitness and nutrition decision-making. It’s not about creating professionalism (I just don’t have that kind of leverage.) I’m not a policing agent to expose the charletans on the Internet–though I suppose my blog posts do read that way a little (or a lot.) All I can do is what I think I’m good at, which is to give you as good of an interpretation of the science that _is_ used in justifying why you should change the way you live in striving for a better life.

That, and help scientists design methodologically sound studies. Seriously, scientists: Contact me.