My tennis elbow protocol: For posterity’s sake.

A long time ago, but not so far away, I did a PhD. My area of expertise is primarily in research methods and biostatistics, but you can’t do a degree in methods and stats without a content area, so my content area is musculoskeletal health–which does carry over to what I do now (how about that?) Since I wanted to focus on developing and experimenting with new research methods and analytical techniques, I picked a disease that was very common, so that I wouldn’t run into recruitment issues; because there’s nothing worse than putting a year’s worth of work into writing a protocol, getting ethics approval, funding and everything in place only to find that it’s going to take the next 8 years to meet your sample size. So to avoid this problem, I picked tennis elbow, because everyone and their dog has tennis elbow. And there are no magic bullets to treat tennis elbow.

I learned a lot in that PhD (there’s a mild understatement.) I keep learning now. But out of that PhD arose my opinion on how to treat tennis elbow. At one point, there was a post on jpfitness.com that outlined the protocol, but it seems to have vanished. And recently, Scott Baptie was interested in at least reading about it and I had no where to point him. So, for posterity’s sake, here’s my protocol for tennis elbow.

I should mention the standard disclaimer that while _I_ use this protocol as medical advice for MY patients, that chances are, you are not my patient and therefore, if you follow this protocol and get hurt (though I don’t know how), or don’t get better, or get worse, it’s not my fault or responsibility because I have no patient-physician relationship with you (unless you’re already my patient and reading this) and I have no way of verifying your diagnosis and the suitability of this protocol for YOU. (It’s a little weird not being able to cut and paste a standard disclaimer about stuff not being medical advice when you’re a doctor…)

This protocol stems from a few pieces of research as well as the randomized controlled trial from my thesis. I still think what we think of as tennis elbow as possible several diseases that we haven’t been able to really tease apart, which is why some therapies work for some people and not others–because although they experience the same elbow pain, their causes might be different.

It’s more or less accepted that tennis elbow is not an inflammatory disease. We consider it degenerative, or non-reparative, for the most part, hence the veering away from using terms like “tendonitis”, which, in the current language, implies inflammation. There is good evidence to show that in many patients who have tendon pain, that on ultrasound there are tiny “neovessels” that have grown into the tendon, where presumably there were none before. Additionally, these vessels do not appear to be present in people who don’t have tendon pain. Obliterating these neovessels is linked to pain relief. Several studies on painful eccentric exercises have been shown to improve pain of Achilles tendinopathy, and so this protocol is basically structured off of that one.

The protocol involves a stretching component, followed by the eccentric component , and the repeating the stretching component. The protocol should be performed 3 times a day, at least 5 days a week.

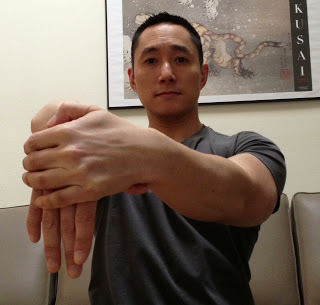

Tennis elbow stretch:

Start in the position as shown below. The hand that is doing the stretching should always have some pressure to flex the wrist down. Slowly straighten out your elbow while maintaining the same pressure on your hand to keep the wrist flexed. Once straight, hold this position for 10 seconds. You should feel a stretching type discomfort in your elbow where it usually hurts. Then SLOWLY return to the starting phase.

|

| Starting position |

|

| Finish position (front view) |

|

| Finish position (side view) |

Repeat 5 times.

Tips: If you straighten or bend your elbow too fast, this stretch usually ends up being more painful than it needs to be.

Eccentric exercise:

Get a soup can and a grocery bag. You should be seated at a table where you can hand your wrist off the edge, while keeping your whole forearm on the table. Pick a table where the soup can isn’t going to smash into the table. The exercise starts at the bottom. Slowly bring your hand up, extending your wrist, similar to a reverse wrist curl. Once at the top, let your forearm relax so that the can inside the grocery bag drops under the force of gravity. This is a fast movement that requires no effort on your part. The goal is to hold onto the bag and let the weight of the can drop your wrist. This may be quite painful at the elbow, but go through the pain. This should not be painful at your wrist or shoulder. If it is, you’re either not doing it right, or you have other problems.

|

| Start position (There’s a can of soup in the bag, honest) |

|

| Wrist extension position. From here, let the weight of the bag drop your wrist down |

Perform 3 sets of 10 reps.

Finish off with 5 elbow stretches as above.

As with any of the tendinopathies, this protocol takes about 12 weeks to really work. Most of the time, tennis elbow burns out no matter what you do (in my opinion), though this can take 1-2 years to really happen. Most of my patients end up at least with improvement by the 12-week mark, as far as I can recall.