Evidence and innovation: Behind or not?

Spurred on by Bret Contreras and a Facebook link from Lars Avemarie, “If you are truly evidence-based, you’re only as good as somebody else was 2 years ago,” I figured I would brush this draft off and publish it.

The story of Margaret Wente’s Dupuy hips was what originally inspired me to write about this issue. Ms. Wente is a writer for the Globe and Mail, one of Canada’s main newspapers. In 2006, she wrote a piece on her journey through the Canadian health care system to get her hip replacements. She talked about how she used Google to find out that the standard hip replacements at the time in Toronto (where she lived) weren’t the ‘…only or even the best one(s)…’ She also learned about a ‘new’ technique called ‘hip resurfacing’ which promised her a faster recovery, and longer implant lifetime (switching out an implant is not simple.) She found a Canadian surgeon who was able and willing to do the procedure for her, and she got two Dupuy implants. The tone of her article was, “Do your homework because you might not be getting ‘the best’.”

Fast-forward to 2013 and back to the Globe and Mail. Things hadn’t gone as promised. Ms. Wente wrote a second article, “The nightmare of Margaret Wente’s miracle artificial hips” in which she recounted her experience but also revealed the fact that the “best” replacement had subsequently been found to have higher failure rates than the industry-accepted standard. In fact, in 2010, Dupuy issued a recall on its implants. At the end of her article, she wrote, “I’m sorry I wrote that piece in the paper, and I worry about the people I encouraged….”

Evidence is almost always behind new and exciting trends. What we do as researchers isn’t really all that glamorous. There’s nothing breaking-edge about a randomized controlled trial from the perspective of the intervention. You just can’t justify the massive resources that it takes to run most trials on interventions that are _that_ experimental.

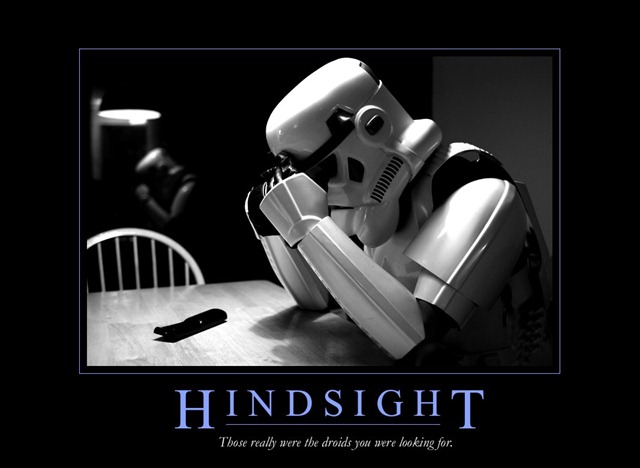

However, I find the original statement, “If you are truly evidence-based, you’re only as good as somebody else was 2 years ago,” as a very short-sighted and ignornant perspective. Things that are breakthrough/cutting-edge are only shown to be so in hindsight. They can never be truly revolutionary while they’re being introduced. It actually takes study and evidence-creation to show that they’re revolutionary.

Tabata wrote his interval-training article (for the intervals that now bear his name) in 1996. The article, “The Tabata Method” appeared in T-Nation in 2004.

In 1999, the BOSU ball was invented. It didn’t really take off until 2009 after Lance Armstrong was photographed using one in Men’s Health magazine.

Fast-forward to 2013. Both of these trends were considered “breakthrough” techqniues/devices in their time. While Tabatas (after several clarifying articles on what actually consitutes a Tabata interval) are still in wide use, I can’t think of many fitness industry-leaders who recommend the use of a BOSU ball. In fact, there are at least two studies to show that there are no advantages to using the BOSU ball over using stable ground. Conversely, there are at least two studies with Tabata-like protocols showing improved outcomes for fat loss, as well as fitness.

So, in 2006, if you were a BOSU proponent, you might have been lauded as being ‘ahead of your time’ and ‘in front of the evidence’. In 2013, there aren’t many places where that position would be considered laudable. The reverse might apply for an early adopter for Tabata or Tabata-like training. Aerobics (remember the 20-minute soft-porn?) had a stranglehold on ‘revolutionary’ for over 2 decades. But it’s only looking backwards from 2013 that we can draw the conclusion that someone or something was visionary.

Margaret Wente thought she was getting the ‘state of the art’ hip replacements in 2006. And in 2006, despite the deep divide within the orthopaedic community, the popular opinion amongst consumers was, “new is better.” Revolutionary at the time, abject failure after the evidence was collected. And it’s not just Dupuy hips: the Artelon implant and the “orthosphere”, both for basal thumb arthritis; total wrist replacements; even some drugs; all lauded for their promising initial results, and today, not worth the paper their studies were published on. It’s not just fitness that this faulty mindset lives, but in any field where sensationalism has the ability to overrule reason (and patience) and where there is substantial reward for offering something your competitors don’t or can’t.

So, to practice in a true evidence-based fashion might put you “behind” by 2 years, but it’s not for at least 2 years that you would know that you were “behind”, or actually just “not duped”.

EDIT [Aug 12,2013]: This isn’t to say that you can’t or shouldn’t be an early adopter. The problem, however (and this is a problem in many fields including fitness and nutrition) is when there’s no accumulation of systematically collected data during the early adoption or development period to enable/facilitate evidence creation. It’s one thing to say, “Look how this worked on client A, B, E, F, G, I, J, K, O, Q, R, S, T and W, with photos/videos!” It’s another to say, “Here’s how I picked the clients A-Z; here’s how I collected the data and as a whole, it worked!” even if you never publish it as a journal article. If you’re going to be a knowledge developer, and stay ahead of the curve, then it behooves you to demonstrate that your curve pans out when those of us ‘behind’ test it out. Otherwise, you’re not revolutionary, you’re just sensational.