Are your fitness decisions fully informed?

Everything we do shapes our opinion of effectiveness. The opinions of others also shapes our ideas of effectiveness. And while your own recall of what works and what doesn’t work likely falls on the side of the majority of the time (if you prescribed intervals vs steady-state cardio for a bunch of clients, and most of them lost more fat on intervals, chances are your recall bias is unlikely to think that steady-state cardio is the way to go), it is nonetheless, biased, because you are also less and less prone to prescribing other things when you think you’ve found the thing that actually works. And sometimes you remember the dramatic cases preferentially, when it’s the other thing that works most of the time.

From a “public health/fitness” point of view, it’s also a waste of time and resources for 1000 fitness professionals to individually try the new thing against their old thing when the new thing is shown not to have an advantage over the old thing in a well-conducted, unbiased, generalizable study. Even if it takes just 10 clients to figure out the new thing isn’t really worth doing, that’s 10 000 clients who just wasted however much time it took (likely at least a month) for their fitness professional to figure out it wasn’t worth doing. And that’s assuming that there are ONLY 1000 fitness professionals who adopt this approach.

There is a trend in medicine. It’s called Evidence-Based Medicine. It’s such a popular trend, that it’s not even optional in medicine. Every major certifying exam in medicine has a component of “EBM” in it, worth as many marks as the question on how to cut open a belly, which drug to give to someone in rapid atrial fibrillation, or how to tell if someone has “flesh eating disease”. As with all things that are mandated, EBM is always regarded with mixed (or not so mixed) feelings–usually a mixture of loathing, hatred and confusion. We, of the firmly-in-the-EBM camp, have struggled to make the EBM approach to medicine more palatable and accessible, and sometimes, compromising our ideal goal of everyone having as much understanding as we do of the issue–much like how the recommendation of 20 CUMULATIVE minutes of exercise per day having an incremental health benefit really does just compromise the whole goal of making people, in general, less fat. People, in general, view exercise like bland rice cakes. They’re about as exciting and tasteful as cardboard. There are some people in this world who LOVE bland rice cakes and cardboard; and in a world where bland rice cakes are being mandated, bland rice cake lovers are trying to figure out a way to make them at least tolerable; because we know you’ll never love bland rice cakes (or in some people’s case, plain tilapia and broccoli) as much as we do.

So why is this relevant to you? And more importantly, how does “evidence” (which may or may not be formalized research) help inform your decisions? To this end, some of the people who are smarter than me, have come with a “new” framework in which EBM (and hopefully, EBF) can be practiced in a sane, practical and useful manner.

EBM has traditionally been viewed as an “us vs. them” approach to medicine. The practitioner feels compelled to change their practice based on some sort of evidence and often feels at odds with their personal experience and clinical acumen. Sometimes, this is justified–why fix something, that in your mind, isn’t broken?It’s interesting to see how physicians interact with research evidence because this “us vs them” mentality is still very prevalent. Yet, if you were to talk to someone who is genuinely comfortable with the EBM philosophy, none of them see it that way. The researchers aren’t trying to take over the world–not yet anyways. But for whatever reason, it took a fairly talented writer and one of the big Kahuna’s of EBM, Gordon Guyatt, to succinctly frame what we have all been thinking for years yet have been unable to express adequately to our colleagues.

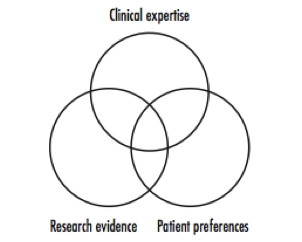

The current model looks a little bit like this:

This model pits clinical expertise against research evidence. Clinical decision making occurs in the tiny intersection where clinical expertise, research evidence and patient factors intersect. This means that large parts of clinical expertise are distinct from a large proportion of research evidence, and vice-versa.

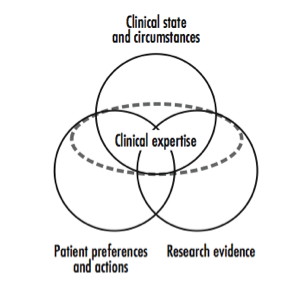

But as Dr. Guyatt so elegantly frames it, there is room for a newer paradigm:

The “new” model basically redefines what it means to be an expert. It is an integrated model–one in which clinical expertise is comprised of knowledge of the patient’s body, physiology and disease (Clinical state and circumstances); the patient’s preferences and research evidence. The clinical decision, therefore, is a true decision and not a substituted decision, overridden by the research.

By this token, a decision that is based on expertise that does not include research evidence can be viewed as an incompletely informed decision. It is a decision that is largely based on biased recollection of personal (and perhaps somewhat limited) experience and on knowledge that may or may not be current! It is what we might call “dogmatic” practice.

In terms of being a trainer or a coach, this paradigm doesn’t really change much. As a fitness professional, program design decisions are largely influenced by personal experience (both as the trainer and the trainee–which is a perspective that most physicians will never have); formal and informal ongoing instruction, which is largely self-selected (i.e. you tend to choose to be taught by individuals who share your training philosophies as opposed to those who have different ones); and your educational foundation (e.g. whatever textbook you used in your certification exam, or the undergraduate degree you might have in a kinesiology-related field that supplied you with basic physiology-type knowledge). Program design is further modified by client preferences and realities (e.g. you cannot design a 5-day a week program for someone who cannot train five days per week; you cannot design a program that requires 2-hour sessions if your client can only realistically train for 45 minutes per workout; and you can’t really recommend that your client increase their milk intake if they’re lactose intolerant).

However, I would argue that if you’re not taking in some sort of systematically conducted research into your programming decisions for your clients, that you’re making decisions that are fundamentally incompletely informed. I think given enough clients, and enough time, any trainer can probably build a “successful” client base, on the same basis that every medical school class in North America has great grades–your fitness practice simply self-selects for “excellence” because those clients who experience positive results will stay with you, while those who don’t will leave you and thus, won’t ever really show up on your “training failures” radar. These “successful” trainers succeed in spite of their decisions, not because of them.

So what does research get you anyways? Minimally biased research gives you the perspective that you don’t have (and in some cases, don’t want). It attempts to evaluate decisions in an objective, unbiased way, such that the failures are counted in with the successes, so you’re not blinded by the self-selection bias that exists in your own “practice”. The downside to this paradigm is that it demands a baseline of research literacy that is not something that currently taught in certification programs, or even sufficiently at the undergraduate level (medical or otherwise). So if you’re serious about making fully informed decisions about your clients and using the full extent of the resources that are available to you; perhaps you might consider spending _some_ portion of your time learning about becoming research literate.

References:

1. Haynes RB, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH, Clinical expertise in the era of evidence-based medicine and patient choice. ACP J Club. 2002 Mar-Apr;136(2):A11-4. Figures stolen shamelessly from this editorial