An iPod Shuffle! For almost free! (Oh, and protein timing)

Eating protein before and after workouts has been touted to be one of the most important things you can do to decrease DOMS, increase protein synthesis, prevent protein breakdown, and in this article, increase your resting metabolic rate. The other claims…maybe I’ll tackle those another day (This post is hellishly long enough)

There are many reasons to increase muscle mass. For one, it makes you look more attractive (for the most part). Increased muscle mass is usually associated with being stronger. However, increasing muscle mass to burn more calories while at rest (because muscle is more metabolically active than fat) is kinda like saying that ordering a diet Coke with two Big Macs and a large fries is calorie reduction–TECHNICALLY, you reduced the number of calories you COULD have consumed. But then again, you also didn’t order McNuggets on top of THAT, so maybe you could have had that regular Coke after all, if that’s the rationalization you’re choosing to indulge in.

In other words, growing your muscles so that you can eat more (or exercise less, or lose weight faster) is not really where you want to spend your effort (if effort is a limited resource, and for most people, it is) because the benefit is quite negligible.

But I digress.

When to eat your protein lies amongst the magical treasure trove of the mythical muscle growth dragon. And if you take this study at face value in terms of the words they write, the treasure is within grasp. On the other hand, you could just wake up from your dream and see the reality.

Hackney KJ, Bruenger AJ, Lemmer JT. Timing protein intake increases energy expenditure 24h after resistance training. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise 42(5): 998-1003, 2010

Introduction

Individuals who engage in Heavy Resistant Training (HRT) increase muscle mass and strength. We know that resting energy expenditure (REE) increases for 12-72 hours after a heavy lifting workout (even if it may not be by all that much). However, one of the reasons we think EPOC (excess postexercise oxygen consumption) exists is because of the increased metabolic demand of creating new muscle (i.e. protein synthesis). Protein synthesis has been shown to be increased (again, even if it may not be by all that much in absolute terms as opposed to relative ones) up to 24 hours after a heavy lifting workout. So this group of intrepid researchers wanted to find out whether REE and RER (which is the respiratory exchange ratio and an indicator of non-protein energy consumption) went up more if you ate protein vs. carbs before a heavy lifting workout.

Methods

The researchers performed a double-blind, crossover trial between a protein-laden pre-workout drink against a carb-laden pre-workout drink.

A “double-blind” means that two sets of people didn’t know which drink the subjects were getting. Usually it means that the subjects did not know which drink they were getting, and also that the researchers themselves did not know which drink the subjects were getting. However, this isn’t always the case. A crossover trial design means that all the subjects got one of the drinks in an initial experiment, then got the other drink in a later experiment, with about 30 days between the two experiments.

[The paper does not tell us who was actually blinded in this study, whether the subjects could tell the difference between the two drinks by taste or consistency, and whether the researchers could tell which drink the subjects were getting, and who made the drinks?]

There were no explicit requirements for any of the subjects to qualify for the study. They did use resistance-trained subjects (defined as strength training or weight lifting for at least 3 days a week for at least 6 months), but whether this was something they decided beforehand or not isn’t really known.

They measured body composition (with a BOD POD), one rep max’s (bench press, squat, bent-over row, bicep curl, lateral raise, and shoulder press; as well as leg extension, leg curl and triceps extension on machines) and taught the subjects how to use a food log and how the testing would go (if you’ve ever tried any of these, you’ll know that there is somewhat of a learning curve).

REE and RER were measured for four consecutive days, all at 0700h. The first day was a baseline measurement. The second day, the subjects drank one of the drinks 20 minutes before a workout [They don’t tell us how they decided who to give which drink.]. The protein drink was 18g of protein, 2g carbs, 1.5g fat. The carb drink was 1g protein, 19g carbs, and 1g fat. Both drinks are available commercially. The workout was standardized for all of the subjects and each subject used a weight of about 70-75% of their 1RM.

Statistics

The researchers did the following significance tests:

1. A paired t-test to compare workout volume (sets x reps x load) between carb and protein trials

2. A paired t-test to compare REE between carb and protein trials on day 1

3. A paired t-test to compare REE between carb and protein trials on day 2

4. A paired t-test to compare RER between carb and protein trials on day 1

5. A paired t-test to compare RER between carb and protein trials on day 2

6. A repeated measures ANOVA (trial by time) to compare REE between carb and protein trials as well as baseline to day 2, 3 and 4.

7. A repeated measures ANOVA (trial by time) to compare RER between carb and protein trials as well as baseline to day 2, 3 and 4.

8. A repeated measures ANOVA (trial by time) to compare total energy intake (basically how much they ate per day in kJ) between carb and protein trials as well as baseline to day 2, 3, and 4.

9. A repeated measure ANOVA (trial by time) to compare macronutrient intake between the carb and protein groups as well as baseline to day 2, 3, and 4.

Significant results in the ANOVAs were further explored with Bonferroni tests, which is pretty good.

[1 – (0.95)^9 = 1 – 0.63 = 0.37, which is the probability that at least one of their “significant” p-values would lead them to the wrong conclusion. Look here if you need more explanation.]

Results

Nine people were involved as subjects in this study. Six of them were (should that be “are”?) men and three of them, women. One man dropped out of the study because he couldn’t hack the lifting schedule, which leaves us with 5 men, and 3 women. The men were, on average 23 years old (plus or minus 3.8 years), and the women were 24 years old (give or take 1.5 years). The men had %BF of 12.6% (plus or minus 7.5) and the women, 26.5% (plus or minus 6.7%)

[That’s about right for the age of your typical grad student. While they did have enough power to detect statistical differences (and more on statistical vs. practical later), the fact that there were only 8 people in this study means the results (if you want similar ones) are only applicable to people who are similar to these 8 people.]

In terms of the things that might confuse issues (i.e. confounders), diets tended to stay similar from one trial to the next. Workout intensity was also similar from trial to trial. Figure 3 in the paper is basically what all the hullabaloo is about:

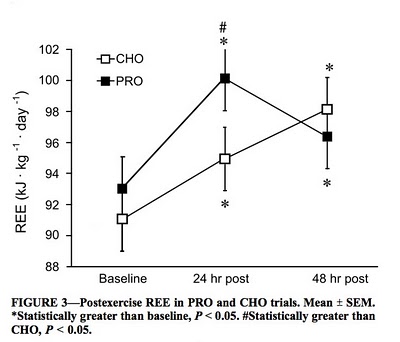

The dark squares represent REE after protein consumption and a heavy workout. The hollow square represent REE after carb consumption and a heavy workout. The * represents a value higher than the baseline value for which p was less than 0.05 in this experiment. The # represents a value that is higher than the other trial for which p was less than 0.05.

As you can see, 24 hours after their first workout, both groups appeared to spend more energy at rest than they were spending before their workout, regardless of whether they had a high carb or a high protein drink 20 minutes beforehand. This higher rate of energy expenditure lasted at least 48 hours. However, at 24 hours, the resting energy expenditure in the protein trial was higher than the carb trial, and this seemed to be a difference that was greater than what we would expect to see by chance alone (p

Discussion

So, huzzah! Drinking 18g of protein 20 minutes before a workout increases resting energy expenditure more than drinking 19g of carb 20 minutes before a workout! Drink that protein! A six-pack and/or slimmer waist awaits you!

Or…save your money?

As we’ve visited before, a statistical difference does not beget a practical or important difference. There are three interesting features in figure 3 (which is what this paper hangs on) that aren’t really discussed in the paper itself.

1) REE went from an average of 93-ish to 100-ish in the protein trial in 24 hours. However, REE went from an average of 91-ish to 98-ish in the carb trial in 48 hours, above the REE in the protein trial at 48 hours. Let’s take an 85kg guy (the mean mass of the male subjects). And since I don’t want to do elementary school-ish math dividing triangles up for areas under the curve, let us assume that the measured REE is the REE for the entire 24 hours:

Protein trial: (93kJ/kg/day x 85kg) + (100kJ/kg/day x 85kg) + (95kJ/kg/day x 85kg) = 7905 + 8500 + 8075 = 24 480 kJ in 3 days

Carb trial: (91kJ/kg/day x 85kg) + (95kJ/kg/day x 85kg ) + (98kJ/kg/day x 85kg) = 7735 + 8075 + 8330 = 24 140 kJ in 3 days

That’s a grand whopping total difference of 340kJ over 3 days. In calories (kcal), that’s…81 calories.

But Bryan, you might say, “Couldn’t you just workout on day 2, and keep the REE at 100kJ/kg/day?” This brings us to point 2:

2) Let’s argue that you can actually do exactly that. The argument forces us beyond what the study can actually tell us, because we don’t know what would happen if instead of doing nothing on day 2, they would have ingested another 18g of protein and worked out. And the black square for that kind of figure could really be anywhere. But, even if that were the case, let’s look at the actual numbers:

The protein trial had an average REE of 100 kJ/kg/day at 24 hours. The carb trial had an average REE of 95 kJ/kg/day at 24 hours. Again, for an 85kg guy, that would be 8500kJ/day vs. 8075 kJ/day, for a difference of 425 kJ/day. In calories, that’s 102 calories per day.

HOWEVER

3) The baseline REE for the two trials was different. Not necessarily “statistically” so, but still different. And on a scale where a “statistically significant difference” is 5 points, a baseline difference of 2 points is an interesting one to think about.

If we take the ACTUAL difference in REE, we see a very different picture:

The protein trial went from 93-ish to 100-ish. That’s an increase of 7kJ/kg/day.

The carb trial went from 91-ish to 95-ish. That’s an increase of 4kJ/kg/day.

For the 85 kg (187lbs) guy, protein caused his REE to go up by 142 calories for a day, while carbs caused his REE to go up by 81 calories for a day. That’s a 61 calorie difference between the two drinks once you’ve adjusted for the difference that they started with.

And what about the drinks themselves? If we take only the primary macronutrient, the protein drink was 18g x 4kcal = 72 calories; and the carb drink was 19g x 4kcal = 76 calories.

Bottom line: No matter how you slice it, I’m not sure 81 extra calories per day (point 1), 102 extra calories per day (point 2), 61 extra calories per day (point 3), or even 142 extra calories burned per day (which is the “extra” you MIGHT burn compared to drinking nothing at all–a very unlikely scenario since we know a workout alone also increases REE) PROVIDED you weigh 187lbs means much of anything (you can do your own math for your own weight, but the benefit decreases with decreasing weight.) If we were to argue that your REE didn’t change AT ALL after a workout, you would only net a 70 calorie benefit in the first 24 hours (since drinking the protein puts 72 calories into your system.) You could simply not eat 70 calories somewhere in your day, not eat anything before your workout, and achieve the SAME effect, while saving the cost of buying those 70 calories AND the cost of buying the extra protein.

How much money do you save? Well, online, the protein powder they used in the study costs $9.99 plus shipping for 13 servings. Shipping is $5.99, so a single serving costs $1.23 USD. That’s how much 72 calories costs. Now, if you’re of the school that “every little bit counts” when it comes to calories and weight loss, that’s 49 days for 3500 calories (1 extra pound of fat) provided you’re already eating under maintenance. Monetarily, that’s $60.27 for that pound. Just for not buying the protein. You can buy an iPod shuffle for that kind of money.

So when it comes to weighing the costs and benefits of timing protein for the purposes of increasing resting energy expenditure and this study, the best timing seems to be no timing at all. And you can afford to buy yourself some tunes and STILL lose fat. How is that not a win-win?