The lime in the coconut is purely optional.

Before I even start explaining what I’ve done here, I want to make it absolutely clear that this analysis is fairly casual, and that by no means have I followed a text-book rigourous protocol to do it because if I HAD done that, you wouldn’t be reading this for another year while it waited in the publication queue of some nutrition journal. However, I will say that even with that disclaimer, I’ve probably been a bit more rigourous than a lot of crap I’ve read, so…well, there really isn’t anything more to say, is there?

Before I even start explaining what I’ve done here, I want to make it absolutely clear that this analysis is fairly casual, and that by no means have I followed a text-book rigourous protocol to do it because if I HAD done that, you wouldn’t be reading this for another year while it waited in the publication queue of some nutrition journal. However, I will say that even with that disclaimer, I’ve probably been a bit more rigourous than a lot of crap I’ve read, so…well, there really isn’t anything more to say, is there?

Back in the early 2000’s there was a small surge of medium-chain-triglyercide (MCT) research that petered out around 2003ish. While there were a fair number of human trials looking at MCT’s and lipid profiles, there were also a handful of trials that also examined the effect of MCTs on body composition, specifically fat loss. And while MCTs are used in some supplements and meal-replacement shakes, there hasn’t been a widespread adoption of MCTs like there was when olive oil got really big (also in the early 2000’s), and I have to say that it’s not entirely clear as to why. Part of the reason might have been the sparseness of human trials involving MCTs compared to those looking at olive oil. Since 2009, however, there appears to be another blip of human trials looking at MCTs, and specifically at coconut oil, or mixes that involve a fair amount of coconut oil.

This review is going to focus on MCT’s and fat loss/weight loss mostly because these variables are the most consistently measured ones in almost all of the studies I found. I’m also going to make a slight departure from individual study review because I think no individual study of the group really makes a strong enough case to start using MCTs. However, as you’ll soon see, doing some data crunching allows us to see a bigger picture that no single study can show.

The theory behind MCT’s is that they’re absorbed in the GI tract but don’t require repackaging into chylomicrons to be processed by the liver. That’s theoretically good because chylomicrons have been implicated in the development of athlerosclerosis. However, what’s more is that MCT’s are also associated with increased fat burning as well as thermogenesis (the creation of heat) as well as lower fat deposition.

Anecdotally, MCT’s have been associated with diarrhea and other GI upset symptoms–which sounds like people taking larger quantities of it all at once. There does also seem to be an association with MCTs and worsening cardiovascular risk factors in larger doses, so more does not seem to be better (as with most things). One of the biggest downsides to MCT’s seems to have been their taste. However, this may be negated with the introduction of virgin coconut oil, as opposed to mixed MCT’s.

If you don’t care how I did it, you can skip to the conclusions (Jump link here, courtesy of Andrew Vigotsky)

Methods

A full-on systematic review takes a long time. Developing a robust search strategy can take weeks, which is why I elected to not do it. In terms of my initial search strategy, I only used PubMed as my database (CINAHL would probably have been a good second one). This started out as a review for coconut oil, so my search terms were pretty broad: “coconut oil” as a keyword search (not mapped onto MeSH heading), and then limited to Human studies. Surprisingly this did not yield a lot of relevant hits, so I also used google for “coconut oil studies”, which was a little more fruitful. I also used the Web of Science database to search forwards from each article to see if any relevant studies had cited the papers I had found. I did find one review paper that summarized MCT oil studies from 2001 to 2010, but didn’t actually synthesize any data.

I decided that I would only consider randomized human trials with supplementation times of at least 4 weeks and measured body weight and body fat weight. There were studies that only looked at weight loss/fat loss over a 2 week supplementation period as well as studies that measured other variables like lipid profiles and satiety, but these were not included in my review.

Analysis

I extracted a few key variables from each paper:

1) The type and amount of oil used in the study

2) The duration of supplementation

3) The change in bodyweight for each treatment group

4) The change in fat mass for each treatment group

In those studies that did not report a direct change number, I subtracted the post-supplementation weight from the pre-supplementation weight. Since the standard deviation was also missing, I used the standard deviation from a comparable study that did report it directly. I used a conversion rate of 0.918 L/kg to convert litres of fat to kg of fat when change numbers were reported in litres, instead of kilograms.

In terms of pooling, I did four pooled analyses. I chose to use a random-effects model because of the supplementation time issue (discussed in the Limitations section). I looked at change in body weight and change in body fat mass for all the MCT studies and then just at those that specifically used coconut oil (or a substantial portion of the mix being coconut oil).

Limitations

Supplementation times were highly variable between studies. The shortest studies were 4 weeks (which was my minimum), and the longest studies were 12 weeks. Unfortunately, most studies did not report interim results at 4 weeks, so a 4-week pooling was not possible. So one of the biggest limitations of this review is that the studies are somewhat heterogeneous, because you should lose more fat over 12 weeks than you do over 4 weeks. However, as you’ll see, this might not make that much of a difference, which then raises a WHOLE other question that I’m not even sure how to get at. More on this later.

Results

In the end, there were 11 studies in total that could be used in a pooled analysis on MCTs and bodyweight loss and fat loss. Five of these involved either pure coconut oil or high proportions of coconut oil. Of these five, only three collected fat mass numbers. One study on MCTs (not coconut oil) reported bodyweight and fat mass changes separately for subjects who had a BMI of less than 23 and greater than 23, which is why it looks like there are 12 studies in the big pool.

Study characteristics

Duration of supplementation varied from 4 weeks (3 studies), 6 weeks (1 study), 8 weeks (1 study),12 weeks (5 studies) to 16 weeks (1 study). Doses of MCTs ranged from as little as 5g to 30% of total daily calories (which is roughly 48-60g). Most studies were randomized controlled trials (7 studies). Three were crossover randomized studies and one was a matched randomized study. Only three studies reported who was blinded and how blinding was performed. No studies reported on sequence generation, sequence concealment or allocation concealment.

MCTs and weight loss/fat loss

|

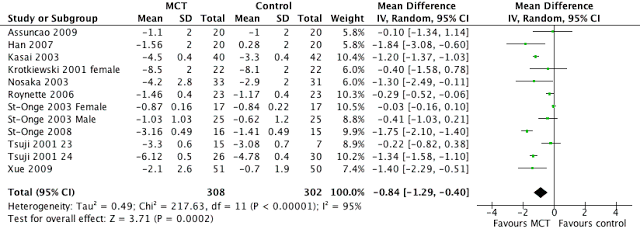

| Mean change in body weight from pre- to post- MCT or control oil supplementation |

|

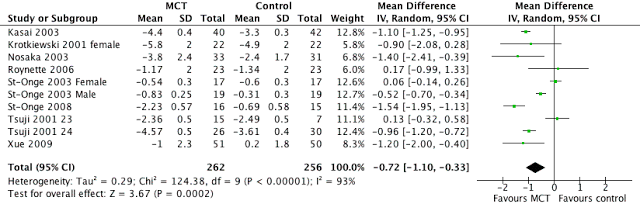

| Mean change in fat mass from pre- to post- MCT or control oil supplementation |

Overall there appears to be a significant effect of MCTs and body weight. The pooled estimate of how much weight was lost on average was 1.34kg. However, what’s interesting is that the pooled estimate of how much fat mass was lost was 0.96kg. So, even though there wasn’t that much weight loss, there was still quite a bit of that weight loss as fat loss. Examining for dose doesn’t appear to demonstrate that either of these two possible confounders has a significant effect on this estimate. In fact, the studies with the highest amount of MCTS tended to sit closer to the 0 effect line, suggesting that higher doses of MCTs may not yield as much of a benefit.

In terms of duration of supplementation, there was definitely a trend towards more weight loss with longer usage, however, this relationship held up less strongly when it came to body fat loss, where one trial (out of three that supplemented only 4 weeks) reported fat loss numbers equivalent to longer duration of supplementation. Oddly, this study (Krotkewski et al, 2001) also used one of the lower doses of MCT oil (9.92g per day). The longest study of the group was 16 weeks, and also reported the greatest amount of weight and fat loss. Of the four studies that had a 12 week duration, one did cross the “no benefit” line (Assuncao et al, 2009), but also had to have the standard deviation filled in because they didn’t report one.

On average, subjects, regardless of gender lost about 0.6kg of fat with at least 4 weeks supplementation. Longer usage appears to result in higher loss of fat, but there is no data past 16 weeks, so at what point fat loss starts to taper off is uncertain. One study (Tsuji et al, 2001) did separate analyses for subject over a BMI of 23, and under or equal to 23, and found that those with a BMI less than 23 did not lose as much weight than those with a higher BMI compared to olive oil, and in the case of fat loss, did not really show a different rate of fat loss compared to olive oil.

However, there may also be a race issue at play as well. All non-Asian studies tended to only include individuals with a BMI greater than 25–most studies included subjects with BMI’s greater than 30. There is fair evidence to show that in Asian populations, a BMI greater than 23-25 indicates increased risk, and therefore all Asian studies included subjects with BMI’s lower than 25 as well as people with higher BMI’s. The observation that less fat is lost when initial BMI is lower was only reported in Asian studies because they’re the only ones that included these subjects. Whether this holds up for all populations or just Asian ones, is not known. It does, however, raise the question of whether MCT’s would have any greater benefit than long chain triglycerides for individuals at “normal” weight. Interestingly, there was a greater reduction in visceral fat (as measured by cross-section) in subjects with BMI

Coconut oil and weight/fat loss

|

|||

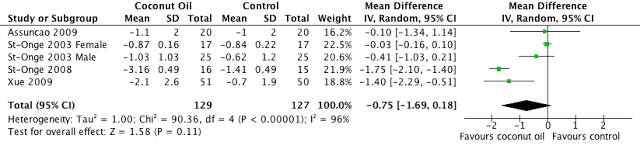

| Mean change in bodyweight from pre- to post- coconut oil supplementation |

|

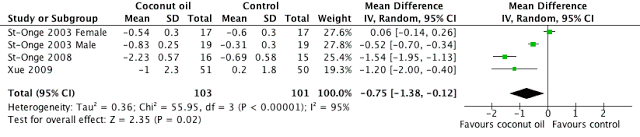

| Mean change in bodyweight from pre- to post- coconut oil supplementation |

23>

There were only five studies that explicitly mentioned exclusive use of coconut oil in the MCT group, or a mix that included a substantial amount of coconut oil.

When it comes to coconut oil, things get a little murky.

Overall, as a pooled estimate, there appears to be definite benefit when it comes to fat loss. , but possibly not with weight loss.

The average amount of weight loss with supplementation greater than 4 weeks was 0.75kg again, with a definite trend towards higher weight loss with longer duration of supplementation, and lower doses of coconut oil. However, the pooled estimate does cross the 0 line, indicating that zero benefit is a possible “true value” (since we’re only sampling a very small part of all overweight people).

Of the five studies, one did not report fat mass loss, and therefore the pooled estimate for fat loss and coconut oil is based on just four studies. The average general amount of fat lost with supplementation greater than 4 weeks was around 0.75kg, though it could be as low as just 0.12kg. When we compare this to just the four studies that measured fat loss, the average weight loss was 0.88kg, paralleling the finding that a higher proportion of the weight lost is in fat. There’s obviously a bias here since the MCT pooled estimate INCLUDES the studies on coconut oil, so it’s not really surprising or fair that everything holds together so nicely.

Only one of these studies was an Asian study with average BMI of 25ish (Xue et al, 2009). They did not report low vs higher BMI results separately, so we can’t tell if the same response/lack of response holds up.

What shows up however, is a possible gender confounder, which may also be modified with duration of supplementation. Of the five studies, two were exclusively female (Assuncao et al, 2009, and St-Onge et al, 2003) and one was pretty close to exclusively female (only 6 men out of 49 total subjects) (St-Onge 2008). Oddly, Xue et al, 2009 didn’t report gender. Both the Assuncao and St-Onge (2003) studies showed basically no benefit to using coconut oil over olive oil for weight loss. Assuncao had a duration of 12 weeks and St-Onge (2003) had a duration of 4 weeks. However, St-Onge (2008), which had a duration of 16 weeks showed the greatest effect in both weight and fat loss of all of the studies. How possible is it that there would be non-relevant weight and fat loss for 12 weeks and then BOOM! dramatic (relatively dramatic) losses between weeks 12 and 16? I really don’t know. This gender difference in effect however, clearly requires more investigation, because we basically have conflicting results from 3 studies (2 of which are out of the same lab) and too much heterogeneity to resolve it at this point.

Conclusions

So after that phonebook of a blog post, what are we to take away from it all?

1) MCT’s, coconut or not, are not going to make your fat loss goals. From a weight loss perspective, the effect is modest at best (losing up to four more pounds over 12 weeks isn’t ULTRA dramatic), but that’s not really news. You already knew that was going to be the case, since we know weight loss occurs because the whole picture comes together, not just which oil you decide to use.

2) However, if you’re a guy, and you can afford to switch to coconut oil and you like it, switching probably has benefits for you in terms of generating more fat loss than if you were using olive oil or another LCT oil. While I’m not generally a big proponent of “every little bit counts”, because it leads to ridiculous complex rules and multiple supplements (i.e. not keeping things simple and sustainable), this particular “little bit”, if you want to use it, is unlikely a hoax.

3) If you’re a woman, it’s not as clear whether switching has benefit for you when it comes to weight loss and fat loss. If you switch to coconut oil, you’d be doing it on the basis of a single study of 49 people (6 of whom were guys) who all had a starting BMI of over 30. Whether or not women who have lower BMI’s would experience benefit really isn’t known.

4) The drawbacks to MCT oils (as opposed to virgin coconut oil) remain the same. While the pooled estimate is tighter than that of coconut oil (by virtue of there being more studies), you’re still going to run into the problems with taste. The problem with switching to coconut oil thinking, “Well, coconut oil is an MCT, so the effects should hold,” is that the triglyceride composition IS actually different. So, I don’t think it’s “safe” to generalize the result from pooling all MCT studies to coconut oil.

5) In terms of dose, it seems that any dose greater than 20-25g per day does not produce any greater benefit. The studies that showed the greatest benefit all used doses around this level, with one study using as little as 14g per day. Going higher may actually lessen the effectiveness, though we have no direct studies to prove this. Twenty-five grams of coconut oil is roughly 27mL (or about 5.5 teaspoons). Women should definitely take less (around 14-18g per day, which is roughly 15-19mL, or 3 to 3.5 teaspoons). I don’t suggest taking it all at once unless you have a really nice bathroom.

6) If you’re going to switch, you should be prepared to do it for the long run, and you shouldn’t decide if it’s not working for you for at least 12 weeks, if not 16 weeks. This is definitely not a fly-by-night kind of trialling. Taking and recording measurements is vital if you’re going to experiment. It’s highly unlikely you’ll see much of a difference after 4 weeks. And if you’re Asian with a BMI of less than 23 already, you may not see one at all for months (we don’t have data past 12 weeks).

7) If you’re going to switch, you should make sure you’re using a pure virgin coconut oil. Be careful that the coconut oil is not a hydrolysed oil (Which is why coconut developed a bad reputation.) Pure virgin coconut oil is solid at room temperature.

On the whole, I would say it’s worth switching (Yes, I’m as shocked as you are). The drawbacks don’t appear to hold up as much for coconut oil as for MCT oils. The possible harms of coconut oil also don’t seem very substantial, particularly at these lower doses, with what appears to be a true benefit (even if the size of the benefit is not mind-blowing).

If you know of a randomized trial that I haven’t put in this review that was published after 2001, please let me know! Also please share your experiences (good or bad) here.

References:

Assuncao ML et al. Effects of dietary coconut oil on the biochemical and anthropometric profiles of women presenting abdominal obesity. Lipids, 44:593-601, 2009.

Han JR et al. Effects of dietary medium-chain triglyceride on weight loss and insulin sensitivity in a group of moderately overweight free-living type 2 diabetic Chinese subjects. Metabolism Clinical and Experimental, 56:985-991, 2007

Kasai M et al. Effect of dietary medium- and long-chain triacylglycerols (MLCT) on accumulation of body fat in healthy humans. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 12:151-160, 2003.

Krotkiewski M. Value of VLCD supplementation with medium chain triglycerides. International Journal of Obesity, 25:1393-1400, 2001.

Nosaka N et al. Effects of margarine containing medium-chain triacylglycerols on body fat reduction in humans. Journal of Athlerosclerosis and Thrombosis, 10:290-298, 2003.

Roynette CE, et al. Structured medium and long chain triglyercides show short-term increases in fat oxidation but no changes in adiposity in men. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases, 18:298-305, 2008.

St-Onge MP, et al. Medium- versus long-chain triclycerides for 27 days increases fat oxidation and energy expenditure without resulting in changes in body composition in overweight women. International Journal of Obesity, 27:95-102, 2003.

St-Onge MP et al. Greater rise in fat oxidation with medium-chain triglyceride consumption relative to long-chain triglyceride is associated with lower initial body weight and greater loss of subcutaneous adipose tissue. International Journal of Obesity, 27:1565-1571, 2003.

St-Onge MP et al. Medium-chain triglycerides increase energy expenditure and decrease adiposity in overweight men. Obesity Research, 11:395-402, 2003.

St-Onge MP et al. Weight-loss diet that includes consumption of medium-chain triacylglycerol oil leads to a greater rate of weight and fat mass loss than does olive oil. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 87:621-626, 2008.

Tsuji H, et al. Dietary medium-chain triacylglycerols suppress accumulation of body fat in a double-blind, controlled trial in healthy men and women. Journal of Nutrition, 131:2853-2859, 2001.

Xue, C et al. Consumption of medium- and long-chain triacylglycerols decreases body fat and blood triglyceride in Chinese hypertriglyceridemic subjects. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 63:879-886, 2009.

Zhang, Y, et al. Medium- and long-chain triacylglycerols reduce body fat and blood triacylglyerols in hypertriacylglycerolemic, overweight but not obese Chinese individuals. Lipits, 45:501-510, 2010.